18 September 2023

Counter-UAS market set for steep rise

Published July 2023 | Asian Military Review Vol 31, Issue 4

Written by Gordon Arthur

Article excerpt below, read full article

The Ukraine war has revealed that C-UAS equipment must now be a fundamental part of any military force. (extract)

Unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) are now a staple for most militaries, but the ability to counter them has lagged considerably.

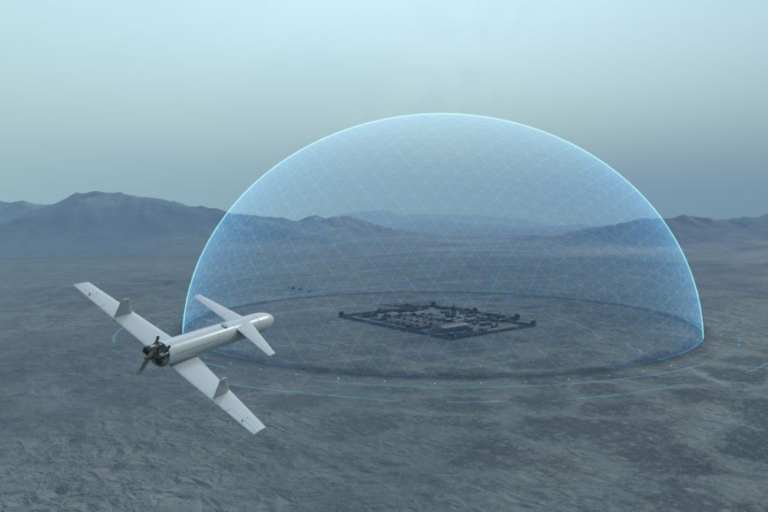

Thanks to the Nagorno-Karabakh 2020 conflict and ongoing Ukraine War, armed forces are belatedly recognising the need to field effective air defence umbrellas against both commercial and military specification UAVs.

Bad actors can also shut down international airports with just a quadcopter, or conduct coordinated attacks with a small budget and little prior training. Therefore, just as UAVs and loitering munitions have burgeoned in the past two decades, so too demand for counter-UAS (C-UAS) systems is set to multiply.

According to Allied Market Research, the global C-UAS market was worth $1.3 billion in 2021, and is projected to reach $14.6 billion by 2031, growing at a compound annual growth rate of 27.9 per cent.

Hard-kill

Hard-defeat effectors include bullets, lasers, high-powered microwave weapons and nets. Australian-based Electro Optic Systems (EOS) is one company offering hard-kill C-UAS systems. Matt Jones, executive vice-president of EOS Defence Systems, told AMR there are huge benefits to using remote-controlled weapon stations (RWS) against both ground targets and UAVs.

Instead of investing in new vehicles, a modern RWS on a legacy platform can instantly and cost-effectively create a C-UAS system.

As can be imagined, numerous rounds fired into the air at UAVs still have to land somewhere. New-generation smart munitions have fail-safe proximity fuses, so Jones said that lightweight 30 mm cannons on EOS’s R400S RWS, and the Bushmaster Mk44S 30 mm cannon on the R800S, are unlikely to create significant damage since their rounds will detonate in the air.

Of course, it is possible to use highly expensive missiles to destroy cheap UAVs, but in wars of attrition where ammunition is finite, simple economics demand their prudent use. This is where directed energy weapons have advantages, since they are only constrained by the maintenance of electrical power.

At the Avalon Airshow 2023, EOS exhibited its 34kW laser engagement system. This modular system “is designed in time to be to be fitted in the back of an 8x8 armoured fighting vehicle as a deployable tactical-vehicle platform. The power level is currently 34kW, we’re actually going to take that to 55kW, and we think that’s a sweet spot in terms of the amount of power and size of the laser,” Jones shared.

The 55kW laser will have a 2.5 mile (4 km) range. “Our program will see the power go up, but also the physical size reduce, as we finalise the design of various subsystems. That’s progressing pretty well,” Jones related.

More powerful lasers give additional range and shorter engagement times. To defeat swarm targets, EOS’s aim is to hit 20 drones per minute, aided by a gimbal that rotates 360° and turns over a hemisphere in less than a second. EOS has fired lasers against hovering drones at 2,600 feet (800m) ranges, and it takes less than a second to knock them out.

Hitting a quadcopter would fry the electronics or cook the battery, but technology is getting smarter about where to precisely engage a larger UAV. EOS boasts of unique beam-steering technology that allows the laser to hit vulnerable wing roots, tail planes or fuel tanks, for example, to cause a structural defeat.

Jones said lasers can be very discriminate in terms of application and power levels. Nonetheless, Geneva conventions regulate the use of lasers to prevent blinding people, for example. Ironically, this plays to the strength of laser systems since they are used to target unmanned platforms.

Jones of EOS spoke of other advantages of lasers. “The benefit with a laser is that engagements happen at the speed of light.” If line of sight is achieved, it can engage a drone. Another advantage compared to guns is that lasers can shoot vertically, whereas cannon systems can shoot only at oblique angles.

Cannons are good at low-level engagements up to 70°, whereas lasers can handle 70°- 90° elevations. Lasers offer longer-range engagements too, beyond the 1.2 miles (2 km) range of cannons.

EOS markets the Titanis C-UAS system that can combine RF detection, camera, radar, hard-kill and directed energy effectors from various suppliers. An agnostic system like Titanis is ideal, since customers may already have jammers or surveillance radars that can be integrated into its non-ITAR C2 system developed by Australian firm Acacia Systems.

EOS has not explored high-powered microwave weapons, but these could potentially be added to Titanis.

Jones said, “The laser or directed energy effector is one of a complementary range of systems. In a military context it has a lot of advantages, but there are always some disadvantages and this is where cannons, jammers and other things fill different gaps.”

Jones concluded, “There is no one solution you can use to counter UAVs, no silver bullet … I think the most important thing is the layering, because there’s not one answer for everything.” Furthermore, the C2 backbone must ensure the right effector is engaging the right target at the right time.